From Ibio to Corrales de Buelna

The house’s unique history

The origins of this house date back to the last quarter of the 19th century and a celebration dedicated to the Virgin Mary that the Dominican fathers institutionalized in the Middle Ages, held on the last Sunday in May.

This holiday, along with its romería, has been celebrated since the 17th century in Las Caldas de Besaya, a locality belonging to the municipality of Corrales de Buelna. It was then that the Order of Preachers settled on a hill on which there was a chapel dedicated to the Virgen de las Caldas.

At these festivities two centuries later, Domingo Díaz de Bustamante, an indiano who had made his wealth trading in the Caribbean and who had recently returned to Spain from Havana, met Felisa Campuzano Rodríguez for the first time. Domingo, who was originally from Herrera de Ibio, had emigrated to Cuba at his older brother’s request in 1817 when he was just 14. He returned aged 53, looking to settle down.

Felisa, herself from Corrales de Buelna, was the sister of the Count of Mansilla, whose ancestral home had a large garden. Domingo would go on to buy a significant amount of the garden from the count so he could build his summerhouse there.

These two events led to the house being built, and a third historical event also explains the type of architecture used in its construction: in mid-nineteenth century Havana, the European emigrants who had made their fortunes through trading sugar, tobacco and other products, built large buildings and mansions, some of which were designed by French architects. It may be that Domingo felt closer to his adopted homeland by building a similar house to the one he had lived in in the Caribbean.

The house’s second owner was Domingo’s son, Felipe Díaz de Bustamante Campuzano, who was an agricultural engineer by trade. Through his marriage with María Quijano de la Colina, Felipe became linked with the lawyer and pioneer of the iron and steel industry in Cantabria, José María Quijano Fernández-Hontoria. María Quijano was the first-born daughter of the latter and Felipe met her whilst spending his summer at Corrales de Buelna.

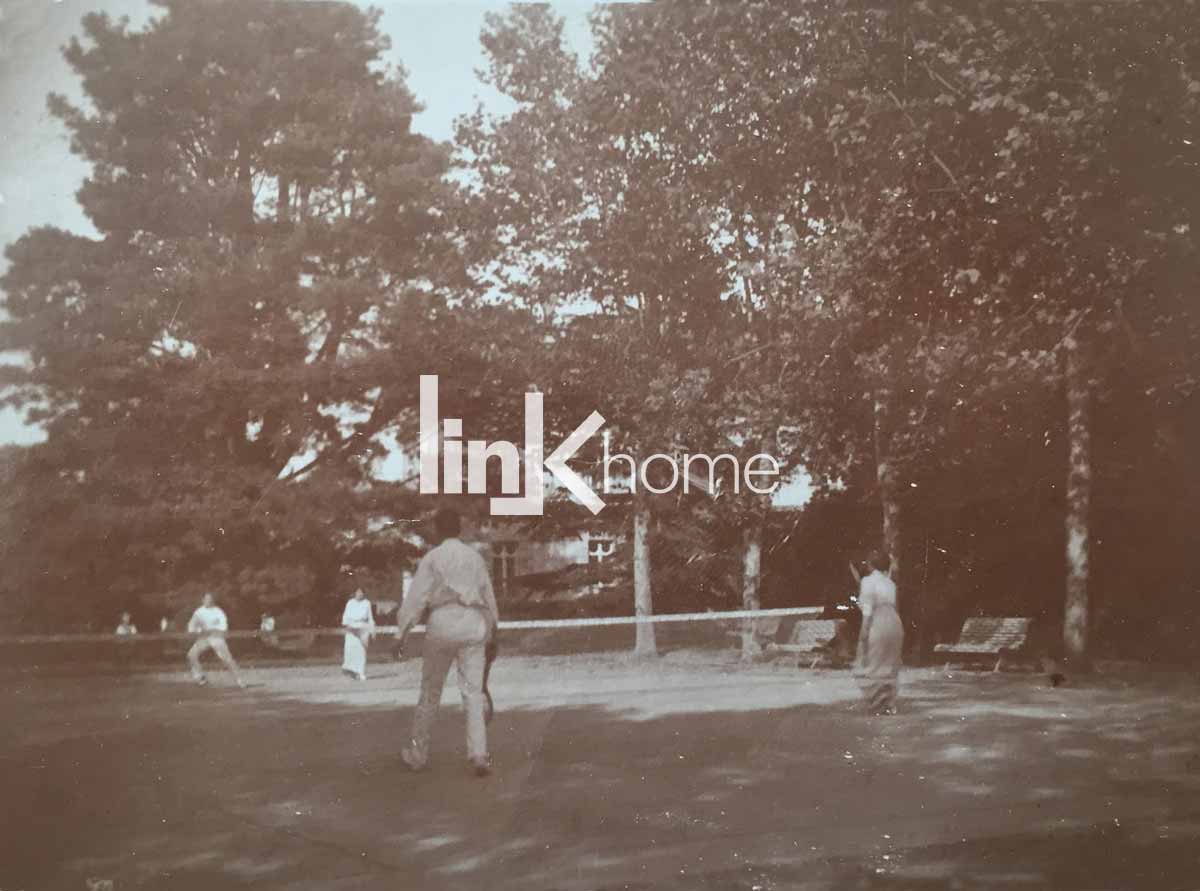

The ancestral home of the Quijano family and the summer house of the Díaz de Bustamante family (who lived for the rest of the year in Madrid) were and still are just a few metres from each other. Both families shared the area, which was only separated by a space called the Rasilla, which is today a town plaza. At the end of the nineteenth century, the plaza contained a field with plane-trees and dust tracks, and as in any mountain town in Santander, there was and still is a dirt bowling alley where lads could be seen playing bowls and still do to this day.

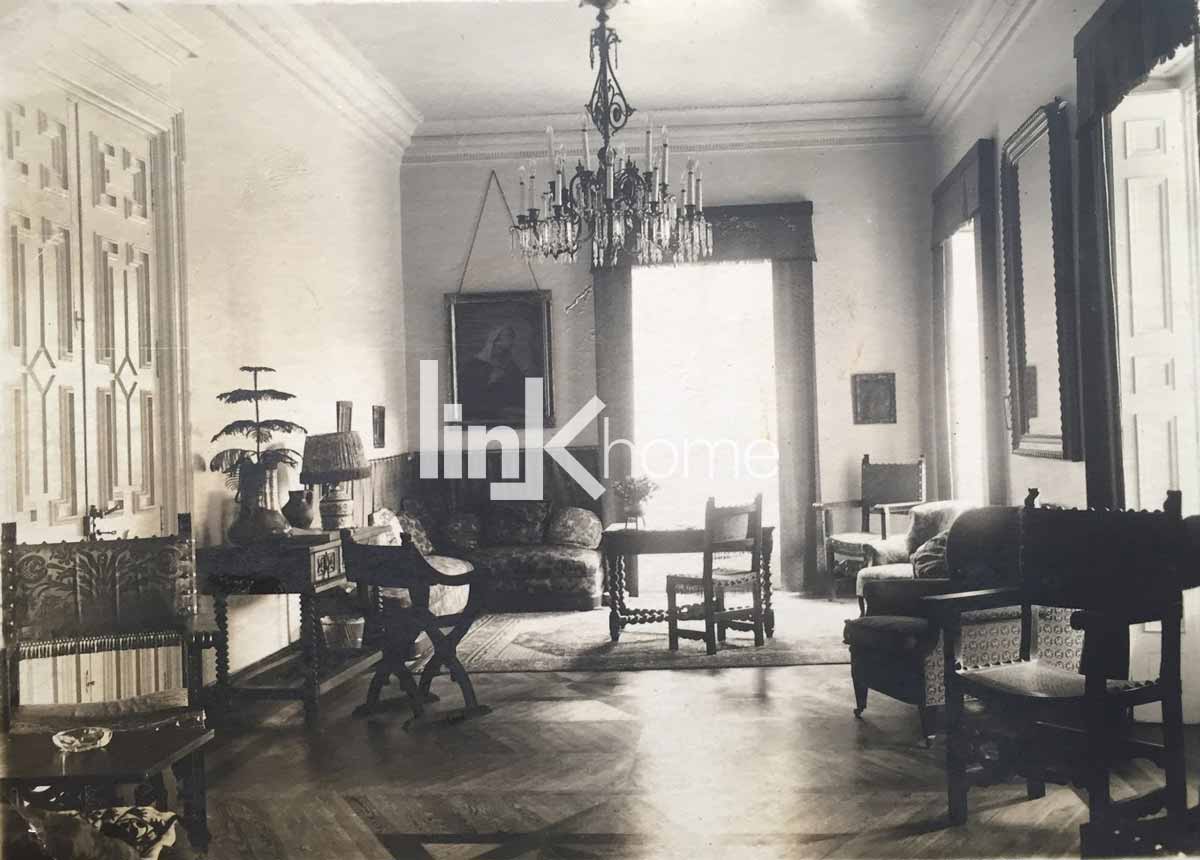

During the Spanish Civil War, the house was used as military quarters and was set on fire. María Quijano, the Indiano’s daughter in law, rebuilt it in the 1940s in its original style.

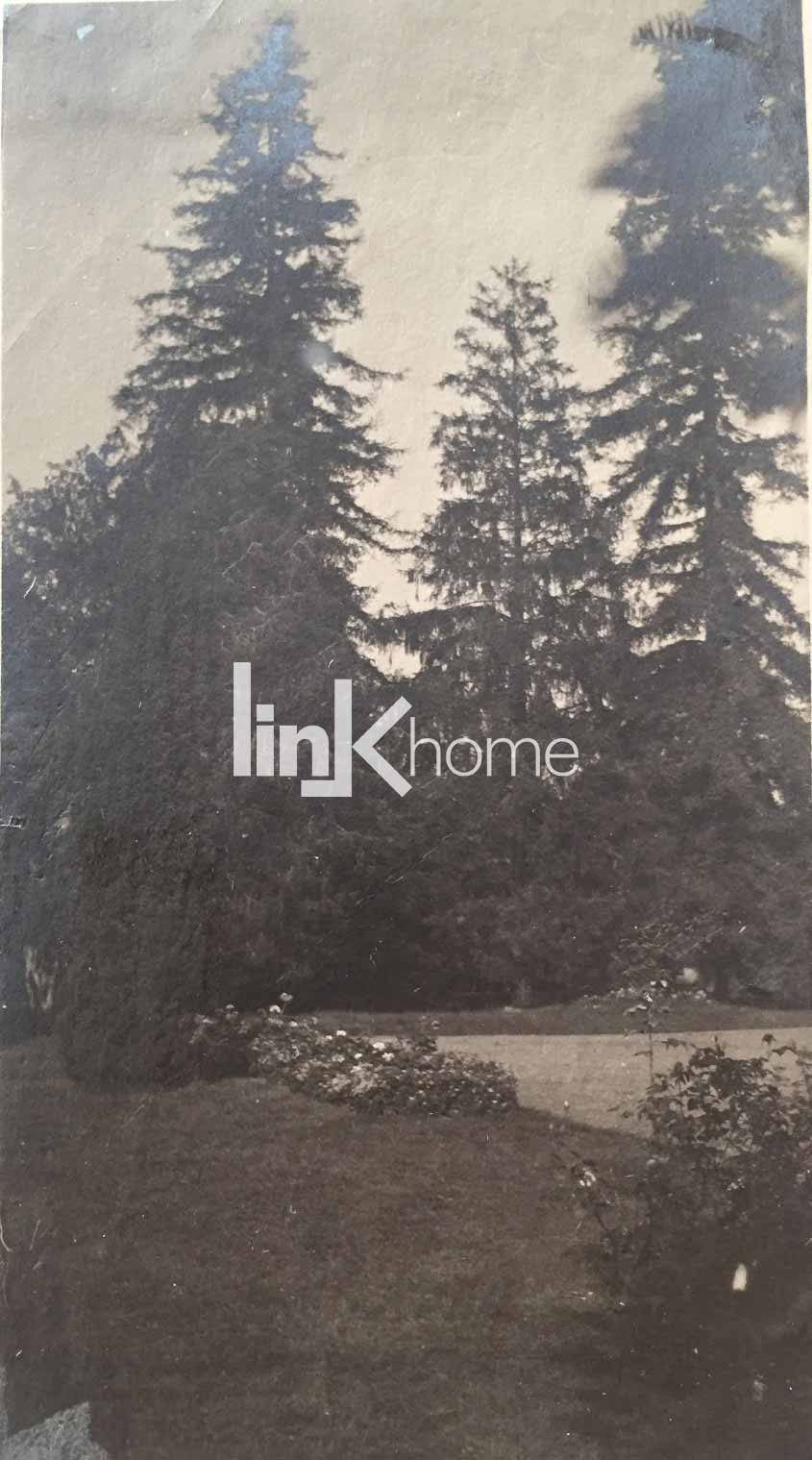

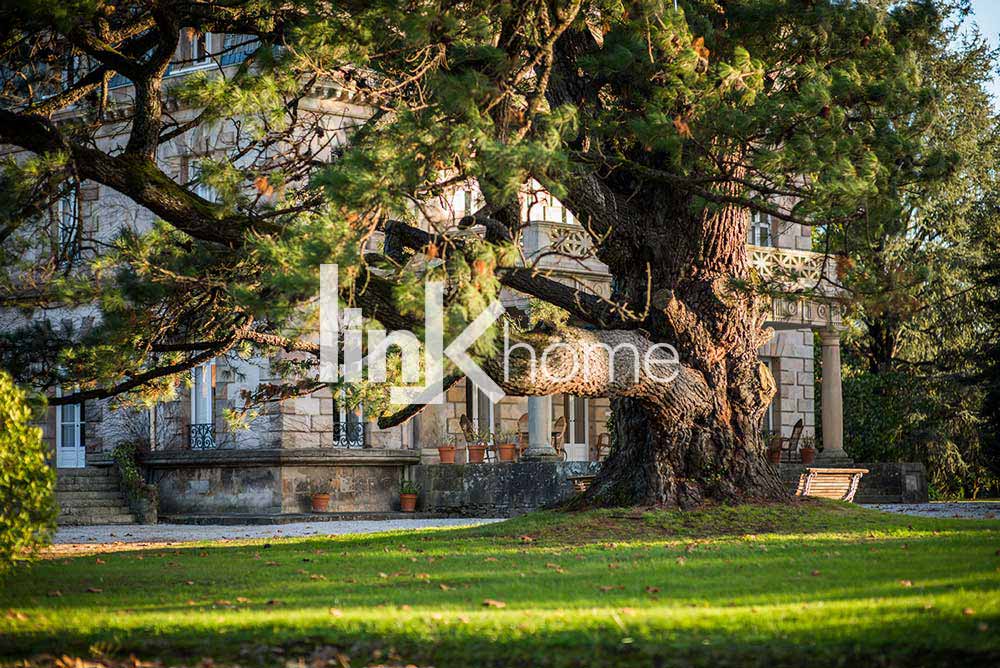

The magnificent garden that surrounds the house is the result of the green fingers of its owners throughout the past century and a half, and several of the trees in the garden are listed as unique specimens in Cantabria.

It is said that a sequoia tree in the garden was inhabited by a family of song thrushes. Their harmonious song was accompanied by that of Sigfrido, a canary who enjoyed Wagner as much as - or even more so than - his owners.

Sigfrido, who was owned by María Quijano, lived in a cage but was taken out onto the terrace every day by his owner. As soon as he felt the fresh air, he would sing to his freedom and his song was met by other birds there. And although an inventory of the songbirds that lived in the garden was never made, Faustino, a gardener who took care of the flowers, plants and pathways for more than half a century, knew that sparrows and magpies would nest in the plane-trees and a hidden nightingale sang from the leafy depths of a yew tree. He also recalled that thrushes, blackbirds, and song thrushes spread themselves out amongst the lime, yew and pine trees.

Today, the garden is majestically presided by a hundred-year-old Pino de Monterrey, that Felipe Díaz de Bustamante planted when he was just seven years old.

Text: Donata Díaz de Bustamante